The phenomenon of deglobalization, however, has roots that predate the outbreak of the pandemic and conflict. As early as 2019, researchers Mario Lorenzo Janiri and Lorenzo Sala highlighted some data that gave a sign of a trend reversal, which began as far back as 2007-2008, at the time of the Lehman Brothers crack.

The value of goods and services exported around the world, for example, grew vertically until 2007, reaching the unprecedented threshold of $20 trillion. Then, however, it fluctuated in the decade after 2007, moving between $20 trillion and $25 trillion. In short, the increasingly free movement of goods and services to every corner of the globe, after a soaring march, has undoubtedly slowed down.

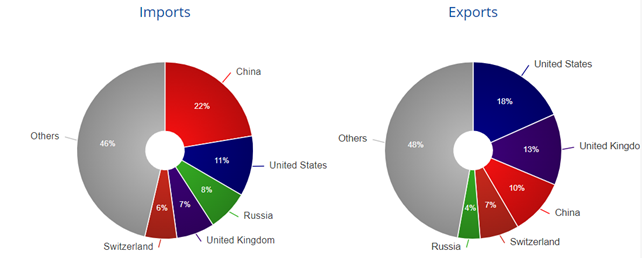

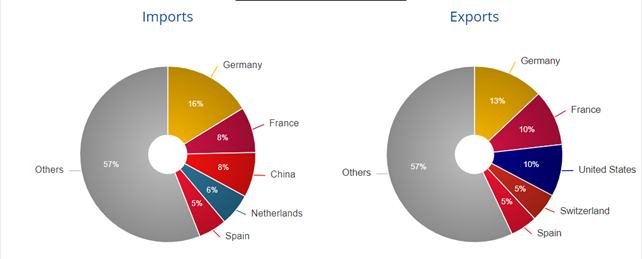

In this context, precisely international geopolitical tensions have then entered the picture, with the war in Ukraine bringing quite a few sanctions on Russia and challenging old trade balances. According to Gianmarco Ottaviano, professor of economics at Bocconi, in the years to come we should not expect "the deglobalization feared or hoped for by many commentators, but (rather) a selective re-globalization, that is, a reconfiguration of the global economy by integrated groups of related countries, coalitions competing with each other for economic, political and cultural hegemony."

Gianmarco Ottaviano, professor of economics at Bocconi

Gianmarco Ottaviano, professor of economics at Bocconi