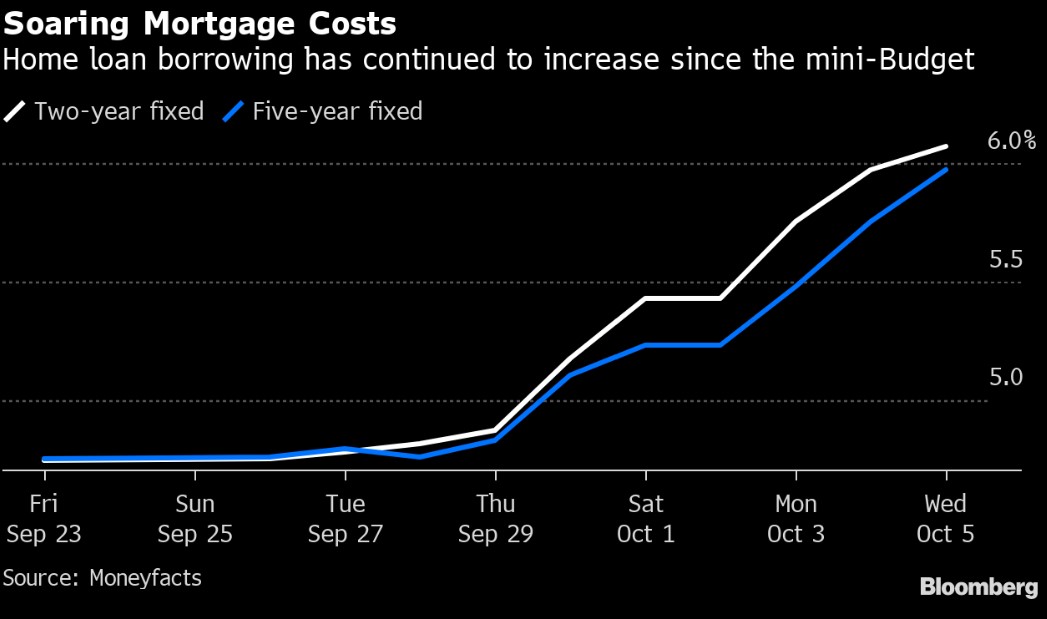

The recent declines, however, are mainly related to a divergence between the Bank Of England's monetary policy and the London government's economic policy decisions. Indeed, inflation in Britain is reaching stellar levels (well above 10 percent) due to rising commodity prices.

To curb high prices, the Bank of England (BoE) raised interest rates, so as to make money more expensive, reduce the amount of money in circulation, and curb consumption and investment somewhat, even at the cost of sacrificing economic growth. In the face of this monetary tightening, the government in London moved in an opposite direction, risking frustrating the central bank's action.

In fact, the maxi-tax cut that the premier partly renounced would surely have stimulated consumption and prices, as well as deteriorated the public accounts, causing a mega budget deficit. That is why financial markets went into a tailspin, with a shower of selling on pounds sterling and U.K. government bonds.

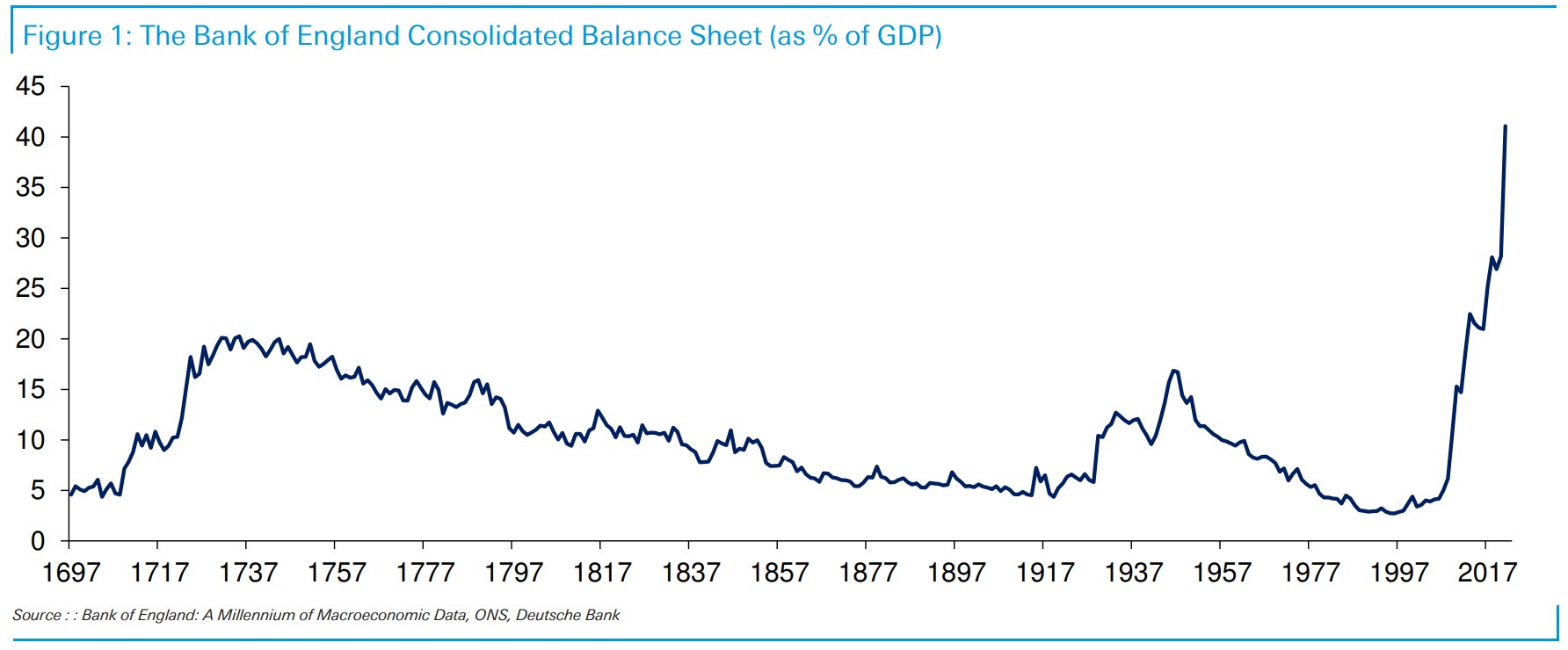

Only the Bank of England has put a patch on it, proceeding to market purchases of government bonds to curb the speculative wave. "The prompt action of the BoE has helped reassure markets at least in part," says Generoso Perrotta, head of Advisory at Banca Generali, who, however, highlights one aspect: "Regarding expectations on the dynamics of interest rates, traders have not substantially changed their view and expect a still decidedly restrictive monetary policy from the BoE well beyond the first half of 2023."

"It is not believed that the situation has currently settled sufficiently," Perrotta continued, "to suggest positioning on the UK curve," as "bond markets will remain on high alert, despite the BoE's efforts to protect financial stability."

"The disorderly movement that has characterized the UK market in recent days," Baldessari adds, "has created a climate of risk aversion that has penalized all risky assets globally. The BoE's intervention has restored calm in the markets, but the extraordinary Gilt purchases will end in mid-October, with the risk that uncertainty about the central bank's next moves and thus the rate curve will return. After heavy declines in recent days, the UK stock market's price-to-earnings ratio is back below the average of the past five years, but many analysts point out that the FTSE remains "uninvestable" until there is clarity on the government's new fiscal policies."

Baldessarri also identifies some longer-term consequences, of the current situation: "The next moves by central banks are still in the direction of more tightening: expectations are for another 75 bps hike for the Fed at its Nov. 2 meeting. This is compounded by the unrelenting strength of the U.S. dollar, which has forced central banks to reach into their reserves to support currencies, spending more than $1 trillion since the beginning of the year. The pressure on financial markets is rising by the day, as witnessed by volatility indexes (VIX, MOVE, etc. ) that have returned to period highs." In this context, it is difficult for Baldessarri to predict what the next "weak link" will be to jump. For sure, investors are already betting on it, exiting emerging market debt (in the last week we recorded the largest outflow from funds and ETFs since March 2020) and corporate bonds, particularly those of lower credit quality."

Paolo Baldessari, Head of Fixed Income & Alternative Investments di Banca Generali

Paolo Baldessari, Head of Fixed Income & Alternative Investments di Banca Generali