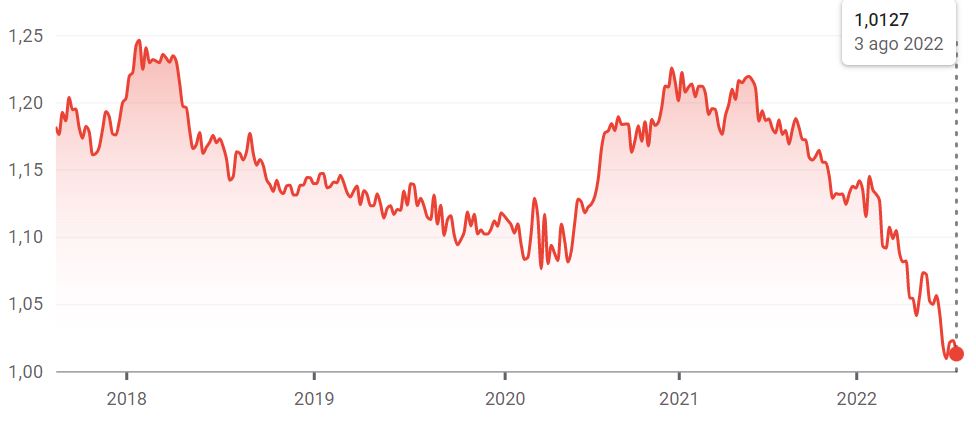

To understand the reasons for the dollar's appreciation in exchange rates against the euro, we first need to take a few steps backward and see what happened in the world economy (particularly in the United States and Europe) between 2021 and 2022, with the easing of the pandemic and the beginning of the war between Russia and Ukraine. In both America and the Old Continent, there has been a surge in inflation, linked primarily to rising commodity prices. Central banks on both sides of the Atlantic are now busy dampening this price flare-up, using the tool they traditionally have at their disposal: interest rate policy.

By raising rates, both the European Central Bank (ECB) and the U.S. Central Bank (Federal Reserve) are trying to put the brakes on consumption and thus on market demand for goods and services. In fact, rising prices (said in broad terms) are generated when there is excess demand for goods over supply in the market. However, in the past few months, international investors have felt strongly that the U.S. Fed was intent on raising interest rates faster than the ECB. This was for several reasons, which economist Carlo Cottarelli explained clearly in an editorial in the Repubblica.

Although inflation is at roughly the same levels on both sides of the Atlantic, Cottarelli explained, in the United States it seems to be a more entrenched phenomenon, as it has "long since spread outside the energy-food sector, while there is now a price-wage run-up facilitated by a level of unemployment not seen in more than four decades." When unemployment is low and there is much demand for labor in the market, in fact, wages also tend to rise since workers have more bargaining power. That's why Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell decided at the last central bank's top meeting to raise the cost of money in the U.S. again by 75 basis points (0.75 percent) bringing it within a range of 2.25 to 2.5 percent. "Inflation is too high. We have to bring it down, at any cost," Powell said, hinting that he was also ready to accept even a slowdown in the economy.

The ECB led by Christine Lagarde also began raising rates, with a 50 basis point (0.5 percent) move at the end of its last meeting. Thus, it is a more modest raise that has brought the cost of money in Europe into a lower range (0.5-0.75 percent). The ECB seems to be more "timid" in its maneuvers because, according to Cottarelli's analysis, inflation in the Old Continent has not yet fully extended outside the energy-food sector and because, on this side of the Atlantic, we do not see that run-up between prices and wages that there is in America. Moreover, Lagarde knows full well that a rate hike has negative effects on European countries with higher public debt that will find themselves spending more on interest. So, if greatly accelerated, high rates risk bringing back among investors a considerable amount of distrust about the resilience of the euro area, as has been the case since 2011 as soon as the Old Continent's economy entered a crisis or a phase of instability.

Carlo Cottarelli, economist

Carlo Cottarelli, economist